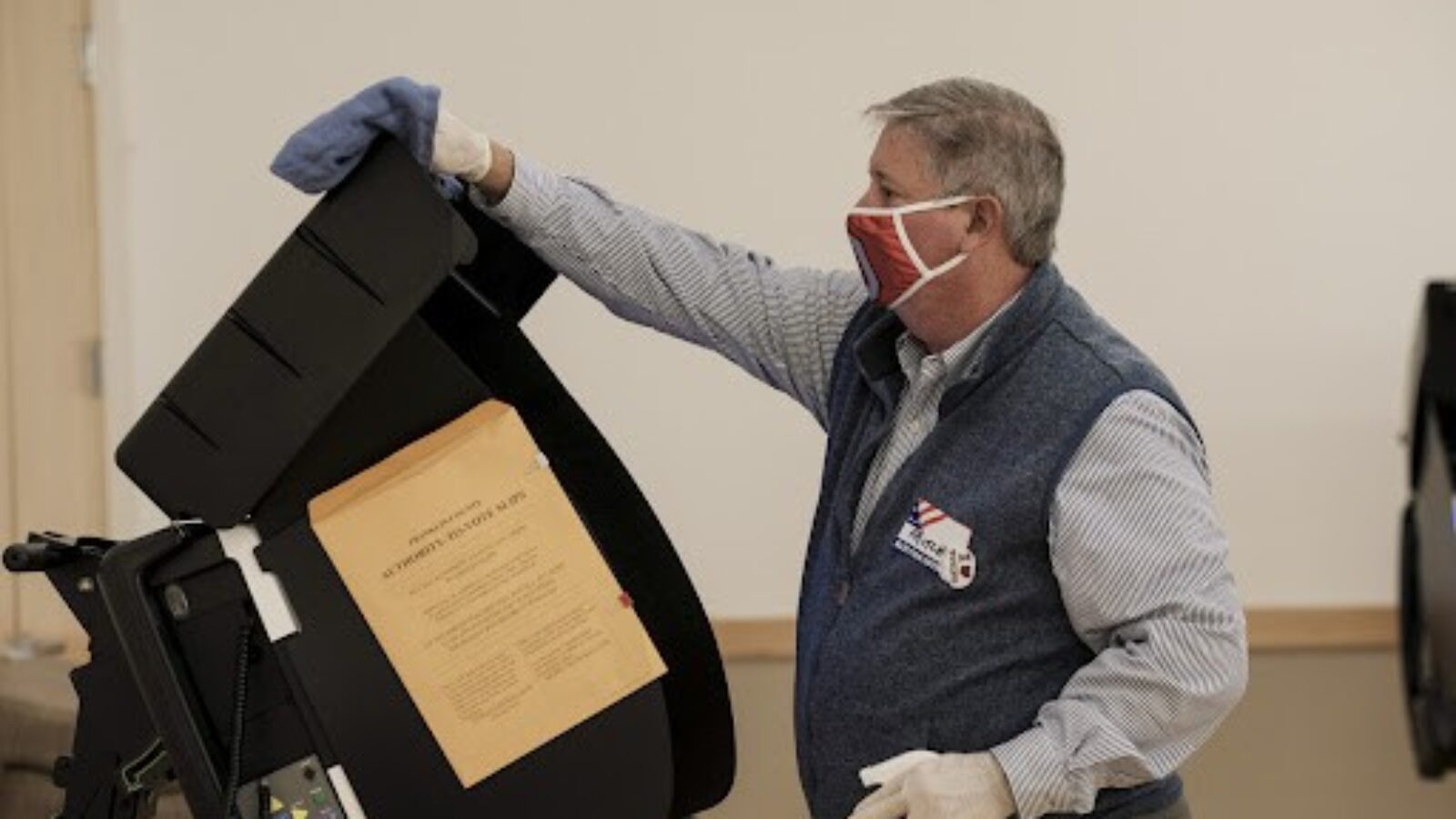

Democrats are worried about an “absolutely terrifying prospect” if conservatives sweep the elections in 2022. A growing pack of Republicans are echoing President Trump’s request that a full audit is performed on state voting machines to ensure that our elections are as advertised: free and fair. Democrats are calling the President’s outcry for total transparency “a threat to our democracy,” which begs the question: what do they have to hide?

POLITICO: ‘Absolutely terrifying prospect’: How the midterms could weaken U.S. election security

Eric Geller; September 9, 2022

Republicans who support former President Donald Trump’s lies about the 2020 election would gain the power to open up access to their states’ voting machines if they win in November — a prospect that security experts call potentially catastrophic for American democracy.

Already, unvetted outsiders have examined voting equipment or inspected the devices’ sensitive computer code in counties in Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Michigan and Pennsylvania, bypassing longstanding security protections — in many cases with the support of Trump allies overseeing local elections. Now Republicans who embrace the former president’s conspiracy theories are running for governor or secretary of state, offices that would give them even broader authority to allow like-minded activists and consulting firms to conduct so-called “audits” of the entire voting systems in key states.

These kinds of examinations would make it easier for hackers intent on sowing chaos or changing the outcomes of future elections to learn how to conduct their attacks, according to voting security professionals, who note that some sensitive information about voting machines has already been leaked since Trump supporters began their push for audits.

It’s “an absolutely terrifying prospect,” said J. Alex Halderman, a computer security expert and professor at the University of Michigan who has repeatedly exposed flaws in voting systems but has also debunked Trump’s claims about 2020 fraud.

For years, physical safeguards such as padlocks and cameras have prevented intruders from exploiting the digital flaws that security experts routinely find in election equipment. But this year’s elections could sweep away these safeguards in key battleground states, in yet another example of fallout from Trump’s baseless allegations of vote-rigging.

Larry Norden, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Elections and Government Program at New York University, said ongoing efforts “to get people in office to provide unauthorized access to election equipment to untrustworthy parties” are putting elections at risk.

Republican candidates promoting Trump’s election conspiracy theories include Pennsylvania gubernatorial nominee Doug Mastriano — who would get to appoint the secretary of state and has said he could order his pick to “decertify every machine in the state with the stroke of a pen” — and Kristina Karamo, Mark Finchem, Jim Marchant and Diego Morales, who are running for secretary of state in Michigan, Arizona, Nevada and Indiana, respectively.

POLITICO requested interviews with all of these candidates. A Karamo spokesperson initially suggested that an interview might be possible but did not arrange one. Efforts to reach Morales’ campaign were unsuccessful. Spokespeople for the other candidates did not respond to emails.

Authorities in several states, including Pennsylvania, Arizona and Michigan, have scrambled to replace election equipment after pro-Trump officials compromised their security. In Colorado, a grand jury this year indicted a county clerk on charges that she had conspired to breach the security of her office’s voting systems. (The clerk, Tina Peters, later lost the GOP primary for Colorado secretary of state.)

Election offices routinely conduct official audits by scrutinizing paper records and electronic data to ensure that the vote tallies are correct, and these offices occasionally give trusted outsiders access to their voting machines to perform security assessments. But the new right-wing “audits” — in which GOP-aligned activists and consultants analyze voting machines’ code, supposedly searching for evidence of election fraud — fall far short of the rigor and accuracy of those sorts of examinations. And they have already produced leaks of sensitive information about how voting machines are designed and how election offices configure and use them.

Voting system hacks could take many forms, cybersecurity experts say. Malware planted on voting machines could cause them to flip votes or simply freeze up during an election. Malicious code could also corrupt the election management systems used to program the machines before each contest.

And breaches in just a few states can endanger security across the country because of how widely used a few models are: Just six voting machine models are used in more than 300 counties each, according to a POLITICO analysis of data from the nonprofit election integrity group Verified Voting. Six models of scanners that tally votes from paper ballots are equally popular.

So-called audits have already compromised machines in Maricopa County, Ariz.; Mesa County and Elbert County, Colo.; Coffee County, Ga.; several counties and townships in Michigan; and Fulton County, Pa.

In some of these jurisdictions, Trump-aligned attorneys such as Sidney Powell have taken the code powering voting machines and shared it with conspiracy theorists and right-wing extremists, The Washington Post reported.

Restricting physical access to election equipment has historically been a vital method for protecting voting machines and the computers used to program them, which for the most part are not connected to the internet.

These election devices contain their share of digital security flaws, as Halderman and other researchers have documented in repeated studies. But election technology vendors have consistently argued that their machines are safe because they’re hard to access and analyze.

One leading vendor, Election Systems & Software, says on its website that its machines are protected by “locks, restricted access, tamper-resistant seals, chain-of-custody protocols and voting machines which are locked down to ensure limited access.” In a statement, ES&S spokesperson Katina Granger said physical security was “vital to ensuring critical infrastructure is not unknowingly accessed and manipulated.”

Security experts have long been frustrated by the industry’s “hard to access, hard to hack” argument, which vendors have used to block legitimate researchers from freely testing their systems. Now, though, conspiracy theorists are gaining access to these devices and copying, sharing and leaking data about how they work, which could make it easier for hackers to find vulnerabilities and exploit them.

The risks have created logistical nightmares for election officials.

In July 2021, Pennsylvania’s secretary of state ordered Fulton County to replace its machines after local officials, under pressure from Mastriano, gave right-wing activists access to them. Maricopa County, Ariz., spent almost $3 million to replace its machines after its high-profile state-mandated “audit.” Other costly breaches have occurred in Michigan, where taxpayers had to pay for new ballot scanners in several townships and counties after authorities investigating the breaches seized the original equipment.

These scattered local breaches could multiply significantly if election deniers win statewide races in November.

In Michigan, Arizona and Pennsylvania, GOP candidates are running to replace Democrats who launched investigations into breaches of voting machines and, in some cases, ordered them replaced.

Election workers would probably try to mitigate the damage from a fringe “audit,” but few are technically savvy enough to spot sabotage, security experts said. “It probably would take very little sleight of hand to make it look like you’re just copying data but actually be tampering with the system,” Halderman said.

Giving unvetted outsiders access could also unwittingly enable more sophisticated sabotage. Foreign spies might plant operatives inside the groups that get access to voting machines to steal information or tamper with their devices, said Will Adler, a senior election technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology, a nonprofit digital policy research group.

Whether it’s domestic tampering or foreign infiltrations, security professionals worry about how little they know about what damage the breaches have already done.

“We just don’t know the scope of what equipment may have been accessed, or even what jurisdictions were involved,” said Halderman. “Maybe we’ll never know.”

Halderman and other experts are pushing for new technologies and processes that would eliminate the need to simply trust election officials and voting equipment. So-called risk-limiting audits, already in use in some states, employ statistical methods to ensure that vote tallies are accurate. Experts also call for the adoption of open-source equipment that anyone could examine for flaws, helping civic-minded researchers stay ahead of malicious actors who may already be gathering that information illicitly.

“Elections today are largely about trust in the officials running them,” Halderman said. “But they don’t need to be that way.”

Photo: Matthew Hatcher/Getty Images