As Joe Biden and Democrats wrap up their closing arguments for the 2022 elections, many Americans are turned off by their divisive rhetoric. With Republicans focusing on inflation, crime, and the southern border, Democrats continue harping on democracy while ridiculing half of the country. Their strategy has not resonated with voters, as Republicans are heavy favorites to retake control of both houses of Congress.

USA TODAY: Why Biden’s closing argument worries some Democrats and could miss the mark with midterm voters

Joey Garrison; November 6, 2022

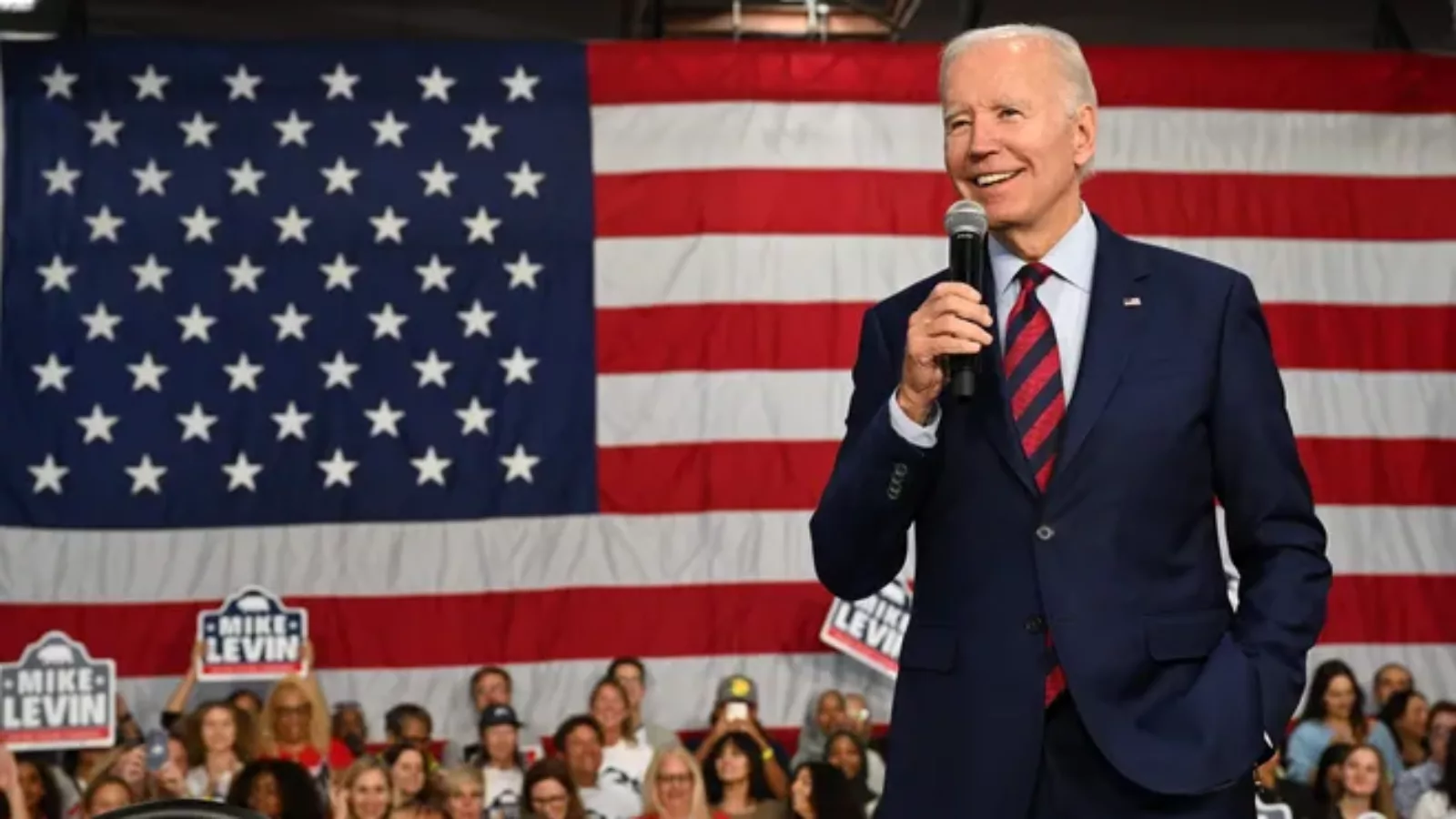

WASHINGTON – Joe Biden crisscrossed the stage for a half-hour before he delivered his gravest warning yet.

The president – his right hand holding a microphone, his left casually in his suit pocket – returned to the podium and paused.

“This is really deadly earnest, man,” Bidentold the Florida Memorial University crowd during a campaign rally last week in Miami. “Democracy is on the ballot this year. Along with your right to choose and the right to privacy.”

Biden has spent the final days of an uphill midterm campaign for Democrats imploring that modern-day Republicans are uniquely dangerous – willing to destroy democracy to gain power, ban abortion nationally, cut Social Security and Medicare and, if they don’t get their way on entitlements, crash the economy by forcing the government into default.

In his closing argument to halt Republican momentum before Tuesday’s election, Biden has painted a dark picture of a possible “mega MAGA Republican” Congress. “This ain’t your father’s Republican Party,” he’s stressedrepeatedly, focusing less on his own accomplishments and more on the intentions of his opponents.

Yet there are serious doubts, including among Democrats, whether Biden’s doomsday portrayal of Republicans has broken through as stubborn inflation and pocketbook issues weigh on voters. Some in the party say Democrats should have touched more on economic concerns earlier in the campaign and less about restoring abortion rights, which dominated Democratic ads for much of the race, in part on the advice of the “governing consulting class.”

“That was a mistake,” said Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., arguing Democrats should compare Biden’s efforts to bring manufacturing jobs home versus Republicans who want tax cuts for corporations. “I’ve been saying for months that we need to frame this election as an economic choice.”

To defy headwinds of 40-year high inflation and the historical trend of midterm losses for the party in the White House, Biden has tried to appeal to undecided voters by arguing “this is no ordinary year.”

“So, I ask you to think long and hard about the moment we’re in,” Biden said in a primetime speech last week. “In a typical year, we’re often not faced with questions of whether the vote we cast will preserve democracy or put us at risk.”

But there’s an underlying challenge with Biden’s depiction of a Republican takeover, according to Lynn Vavreck, professor of American Politics and Public Policy at UCLA: many voters remember previous periods of Republican power in Congress not being especially catastrophic.

“It’s sort of like saying, ‘Trust me, this time it’ll be really different if they take over. The country will never be the same,'” Vavreck said. “It’s a lot of hyperbole. And you’re asking voters to believe something that the past suggests may not be true.”

How Biden has tried to defy midterm gravity

Republicans are widely favored to gain control of at the House, according to most analysts, and have an increasingly stronger outlook to take the Senate, with races in Pennsylvania, Georgia, Nevada and a few other battlegrounds deciding control. Some Democrats have openly discussed fears of a “red wave” election that would deliver a party still dominated by Donald Trump sweeping victories.

Republican control of even one legislative body would be enough to block Biden’s legislative agenda on taxes, abortion, voting reforms and other priorities. If Republicans take over both chambers, only Biden’s veto pen would stand in the way of the GOP passing a host of conservative laws.

Republican candidates have focused their attacks against Democrats on crime in cities, migrants at the southern border and, above all, inflation that’s at 8.2% over last year – even as corporate profits hit a 70-year high. Robert Gibbs, who served as press secretary in the Obama White House, said the “here and now” of inflation has made Biden’s warnings about a GOP takeover hard to stick.

“It’s just tough to make the argument of ‘if these guys get into power, here’s the things they’ll end up doing’ versus, ‘hey, bread was really expensive in Aisle 4,'” said Gibbs, speaking on the podcast hosted by former Obama advisor David Axelrod.

Tuesday’s election is the first national election since the Jan.6 assault on the U.S. Capitol led by Trump supporters. It’s also the first election since the Supreme Court’s decision in June that struck down abortion rights.

“This election is not a referendum. It’s a choice,” Biden has said frequently in a push to make the race not about his popularity, with approval ratings in the low 40s, but instead Democrats’ vision versus Trumpism.

In a final gasp to blunt Republicans’ polling edge on the economy, Biden has taken aim at House Republican leaders who have suggested they might use the debt ceiling as “leverage” to achieve their goals on Social Security and Medicare.

“Now they’ve come forward with a real ticking time bomb. This one is outrageous, ” Biden said in Hallandale Beach, Florida. “Nothing will create more chaos and do more damage to the American economy than playing around with whether we pay our national bills.”

Second-guessing begins

For much of the summer, Democrats outperformed expectations in midterm polling and in congressional special elections, a sign that women and suburban voters were motivated by restoring abortion rights.

But the dynamics appeared to shift about a month ago. A USA TODAY/Suffolk University poll taken Oct. 19 to Oct. 24 found 37% of likely midterm voters ranked inflation as their top concern, compared with 18% who said abortion.

Democratic ads haven’t reflected that trend, however. Democratic candidates and the party’s outside groups have spent a combined $424 million in advertising this election cycle focused on abortion, about eight times the $53 million spent on economic-themed ads, according to AdImpact, a media tracking firm.

Some Democrats are second-guessing that decision.

“We’re getting crushed on narrative,” California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, said in an interview with CBS, arguing Democrats leaned too much into abortion rights, allowing Republicans to win the “messaging war.” He said he worries about a red wave Tuesday. “You feel it,” Newsom said.

Craig Varoga, a longtime Democratic strategist for congressional races, said, “If we have made any kind of mistake, it’s the fact that we haven’t talked about all of these assaults on American freedom.” He pointed to Democrats’ siloed messages on abortion, the economy, and threats to democracy. “We probably should have done a better job of pulling it all together.”

Biden’s speech on democracy at risk was widely viewed as a play to the Democratic base.

“Number one, he absolutely believes it. And number two, it’s a motivator to get Democrats out to vote,” said veteran Democratic strategist Bob Shrum.

But some progressives questioned whether another speech on democracy – his second on the topic in two months – was the right move.

“If you’re going to vote on democracy and the frailty of democracy, if you’re going to vote on abortion, a lot of those people have made their decision,” Faiz Shakir, an adviser to independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, said in an appearance on MSNBC. “The persuasion audience, the people who haven’t decided, they are all in on economy.”

Sidelined from most battlegrounds states

Biden is a full-contact campaigner, known for hugging supporters, telling stories about life in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and giving fiery speeches about the little guy.

But he’s not been at the center of action this cycle.

“Hello, New Mexico,” Biden said last week from a community in Albuquerque New Mexico, hardly ground zero for the midterm campaign despite having one competitive congressional race.

Saddled by low approval ratings, Biden has avoided most battleground Senates states, making no trips in the final weeks to Georgia, Wisconsin, Nevada, Arizona and New Hampshire or appearances with its Democratic Senate nominees. An exception is Pennsylvania, where Biden has roots and Senate nominee John Fetterman has needed help to turn out Black voters.

Biden and former President Barack Obama joined Fetterman for a rally Saturday in Philadelphia. But typically, it’s just been Obama, alone, as Democrats’ chief-stumper in the bulk of states that will decide Senate control.

Obama, speaking Wednesday in Phoenix, lambasted the Republican “cast of characters” running in Arizona.

“If you’ve got an election denier serving as your governor, as your senator, as your secretary of state, as your attorney general, then democracy, as we know it, may not survive in Arizona,” Obama said.

Biden’s 2024 planning underway

A Republican takeover of the House would significantly impede what the White House can pass legislatively for the next two years, perhaps forcing Biden to turn more to executive authority on climate, guns and other areas.

It could also open the door to investigations into the business dealings of Biden’s son, Hunter Biden, which House Republicans have openly discussed, and build pressure from Trump-aligned House Republicans to impeach Joe Biden.

Democrats dread the thought.

“There will be no governing in the House if Republicans take over,” Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., told Politico. “I’m pretty apocalyptic about what the House will look like if Marjorie Taylor Green is in charge. It’s an absolute nightmare if Republicans win.”

A Republican takeover of the Senate and House would be widely interpreted as a repudiation of the Biden presidency, fueling more questions about whether Biden will seek reelection in 2024. Biden has said it’s his “intention” to run but hasn’t formally announced a bid.

Behind the scenes, the president has started to prepare for a reelection campaign in meetings this fall with a small team of his most trusted aides, according to a Biden adviser. Preliminary work, which has explored a Trump rematch and other potential Republican nominees, has included outreach to veterans of Obama’s and Bill Clinton’s reelection campaigns.

“If we weren’t engaged in planning in November of this year, we should be in the political malpractice hall of fame,” Anita Dunn, one of Biden’s closest advisers, said at a recent discussion hosted by Axios.

It’s unclear when Biden will make a decision on 2024, but Biden could face pressure from Democrats to announce his intentions quickly if Democrats lose Congress and Trump enters the race, as he’s indicated he will.

Associates of Trump said they expect the former president to announce his candidacy shortly after Tuesday’s Election Day.

An early announcement this month by Trump wouldn’t affect Biden’s timing on a 2024 decision, according to people in Biden’s orbit.

Although a midterm loss for a second-year president would follow the historical norm, Biden’s circumstances are different than his predecessors: Biden, already the oldest serving president, will turn 80 on Nov. 20. Some members of his own party have said he should serve only one term. And Biden himself has left the door open that he might pass on another run.

Still, those who know Biden insist Democratic losses Tuesday wouldn’t influence his decision.

“Look, I’ve known him for almost 50 years. And he wanted to be president when he was young,” said Shrum, a past consultant for Biden and senior adviser for the presidential campaigns of Al Gore and John Kerry. “Assuming he’s healthy, I don’t think he’s going to walk away.”